Arthur Carhart

While no one person can be called "Father of the Wilderness Concept," Arthur Hawthorne Carhart has been referred to as "the chief cook in the kitchen during the critical first years." Throughout his life he wrestled with issues that still resonate with environmentally aware Americans today, such as the tensions between modernism and anti-modernism and the problem of defining and delineating "wilderness." His contributions to the wilderness movement and his skill at uniting disparate groups, such as conservationists and hunters, toward a common goal are reflected in the organization that bears his namesake, the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center, which was founded in 1993 to foster interagency cooperation in wilderness stewardship.

Born on September 18, 1892 in Mapleton, Iowa, Carhart was an only child who spent his youth tramping through the woods and fields around the family farm. After graduating from high school in Mapleton, he left for business school in Sioux City. At first, Carhart was an ambivalent student who rebelled against his father's wishes and spent his time playing drums with a series of bands in dance halls and bars around the Sioux City area. One of his steadiest jobs was as the sound effects man for silent movies at the Majestic Theater, where he improvised footsteps and gunshots with his drums. In the spring of his second year of school, he returned home to recover from a serious case of pneumonia and, to pass the time, read The Tree Doctor, by pioneer tree surgeon John Davey. The book inspired Carhart to write to Iowa State College to inquire about programs in landscape architecture, where he enrolled soon after while continuing his sideline as a club musician. His degree in landscape architecture, awarded in 1917, was the first ever given by Iowa State in that field.

After an unsuccessful job hunt, a frustrated Carhart enlisted as a musician with the U.S. Army band. During his basic training in Georgia, a medical officer asked if any new recruits had prior experiences with natural or biological sciences. Carhart volunteered, was promptly sent to Washington to train as a medical officer and was eventually placed in charge of an eleven-man laboratory responsible for the safety of the water supply of Camp Mead, Maryland, and the surrounding communities. During World War I, massive outbreaks of food poisoning and digestive disorders were regular occurrences at army camps, with serious illness and even death resulting from polluted food and water supplies. During his two years at Camp Mead, Carhart worked diligently to understand the causes of water pollution and educate his fellow soldiers about the environmental links between the camps and communities and the surrounding areas. In many ways this early experience in the army helped solidify Carhart's environmental attitude and his understanding of the relationships between people and their environment.

In 1919, Carhart married his college sweetheart, Vera Van Sickle, and after an honorable discharge from the army, the Forest Service hired him as its first full-time landscape architect, even though his official title was "recreation engineer." Prior to 1919, the Forest Service Administration did not consider recreation one of its mandates, allowing the Park Service to promote outdoor recreation in the public domain. Therefore, the hiring of a landscape architect represented a major departure for the agency, and Carhart's welcome in Denver could not be considered warm. He was dubbed "beauty doctor" or "beauty engineer" by many of his co-workers. However, his superior, C.J. Stahl, welcomed the opportunity to begin serious recreational planning within their district and gave Carhart free-reign in many land-planning decisions.

After his first winter, Carhart was assigned to spend the summer laying out plans for summer cabins around Trapper's Lake in Colorado's White River National Forest. One evening, after a long day of surveying, as the story goes, Carhart sat by the fire outside the tent of Paul J. Rainey, a well-known outdoorsman who ran the camp where he was staying. After several diplomatic attempts to ascertain Carhart's goal in surveying the lake, Rainey and a hunter buddy finally decided to speak their minds. "Do you have to circle every lake with a road?" they asked. "Can't you bureaucrats keep just one superb mountain lake as God made it?" Carhart realized that these two men echoed his own feelings about his mission. Convinced that the plan to build a road and cabins should be abandoned, he returned to Denver with a new perspective on land management. Impressed by Carhart's reasoning, Stahl accepted the plan and agreed to leave Trapper's Lake as it was.

Carhart's land-planning work with the Forest Service culminated with an evaluation and recreation plan for the Superior National Forest on the Canada-Minnesota border, what is today the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Carhart spent weeks canoeing through the area and listening to both sides of a local debate over access and development. As with his work on Trapper's Lake, Carhart's plan once again proved controversial, if not radical, for the then conservative and utilitarian Forest Service. He recommended that the money to build roads be pulled and that the region remain accessible only by boat.

Modern environmental purists often find fault with Carhart's early wilderness thinking. His was a pragmatic and often instrumentalist view, and yet his insights into the uses and psychological value of outdoor recreation remain perceptive and important even today. He realized that Americans had a paradoxical relationship with the modern world, tearing down and building at a desperate pace while simultaneously dreaming of vacations in the forests and on the shores of quiet lakes. Early on, he maintained strong views on the social value of wilderness and outdoor recreation. More than mere sport, recreation meant spiritual rejuvenation. He wrote, "Perhaps the rebuilding of body and spirit is the greatest service derivable from our forests, for of what worth are material things if we lose the character and quality of people that are the soul of America?"

Although support for his plans remained strong at the regional level, recreation as part of the Forest Service's multiple-use mission continued to be a source of national controversy. Since the bureaucracy moved slowly, Carhart began to worry about the lack of action on many of his land-planning efforts. In December 1922, he resigned his position with the Forest Service after only four years. Oddly, the agency that so frustrated him is now proud to claim him as a visionary, placing him along-side Aldo Leopold in recognition of his contributions to the development of the idea of wilderness.

Soon after his resignation, he joined Culley and Irvin McCrary, a Denver architecture firm, where he spent the next six years. At about the same time he joined the firm, Carhart began, in his spare time, to write short stories, articles for outdoor sports magazines, and landscaping advice columns. By the mid 1920's he regularly published articles in magazines as diverse as American Forestry, Sunset, Outdoor Life and Better Homes and Gardens. Carhart's notoriety as an author of fictional stories expanded nationally, and in 1928 he sold his first novel, The Ordeal of Brad Ogden. It was, fittingly, a tale of a young conservation-minded forest ranger battling a stubborn bureaucracy. The pioneer forest ranger, Brad Ogden, embodied the young Carhart, an idealistic conservationist willing to risk his career to support his environmental principles. Throughout the 1920s, Carhart published similar pieces of western pulp fiction dealing with conservation themes.

Although Carhart spent a great deal of time preaching his pro-environmental message to America via pulp magazines, as with his early philosophy on wilderness, Carhart's environmental fiction displayed considerable ambivalence and contradiction. The most surprising example of this tendency appeared in his second book, The Last Stand of the Pack. Published in 1929, the book chronicles the extermination of the last wolves in the western United States through stories of individual wolf packs and the hunters who eventually exterminated them. In The Last Stand of the Pack, the extermination of the remaining wolves is portrayed as sad evidence of the fading frontier, but is justified because of the need to protect the new civilization that had inherited the West. Perhaps repentant about his unfortunate portrayal of the wolf slaughter, Carhart never again attempted to justify predatory animal control, arguing later for sharp regulations and containment of animal control policies.

As writing began to consume more of Carhart's time, he decided in September 1930, to quit the architecture business and began a career as a freelance writer. Throughout the next thirty years, Carhart dedicated much of his writing and advocacy work to reconciling sportsmen and conservationists. One of the central insights Carhart contributed to the environmental movement over the years was his belief that sportsmen needed to play a role in any successful environmental coalition in the American West. Four books aimed at sportsmen sold well and went through multiple reprints and editions. The most popular, was The Outdoorsman's Cookbook, an unintentionally humorous guide to wilderness cuisine feature such absurd recipes as "armadillo sausage" and "stewed muskrat." The other three books, Hunting North American Deer (1946), Fresh Water Fishing (1949) and Fishing in the West (1950), were practical guides for sportsmen, each laced with a strong conservation message.

In addition to his continued writings, Carhart began in the late 1930s and 1940s to work with various government agencies and environmental organizations. In 1938, he took charge of the newly formed Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Program for the state of Colorado and spent the next five years working on wildlife surveys and coordinating statewide wildlife restoration programs. He later held adviser and board member positions with the Izaak Walton League and the American Wildlife Federation. During these same years, he established ties with the timber industry, then trying to improve its image with sportsmen. Also during this time, Carhart became concerned with the overuse and abuse of chemical pesticides. Although Carhart's writing in this area did not rival the vision of Rachel Carson, she read his work on pesticides while conducting her research for Silent Spring (1962), and the two later corresponded about pollution in the Denver Arsenal and the Lost River in Oregon.

In the 1950s, with the attempt to construct a dam across Echo Park, within Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado, Carhart became a leading local spokesman for the anti-dam movement, along with many other well-known wilderness advocates. The national effort to defeat the Echo Park dam was a watershed for the American conservation movement. For Carhart, the respect he gained as a spokesman for Echo Park provided an expanded national audience for his writings, setting the stage for the success of his five most important books on the environment: Conservation Please! Questions and Answers on Conservation Topics (1950), Water or Your Life (1951), Timber in Your Life (1954), The National Forests (1959), and Planning for America's Wildlands (1961).

Of all of his conservation books, Conservation Please! best demonstrates Carhart's evolving environmental philosophy and also foreshadows the formation of the Denver Public Library's Conservation Library. It featured answers from well-known experts, as well as commentary on all issues from Carhart. Simply assembling all the pertinent questions for the book proved so daunting that he commented, "Any volume which would include all questions must be answered if we are to have reasonably completed conservation achievement in our nation would soon become a library." Throughout the 1950s, Carhart continued to worry about the availability of conservation information, which he saw as critical to the success of the conservation advocacy movement. He strongly believed that his generation of conservationists needed to build a research and advocacy center for future environmentalists.

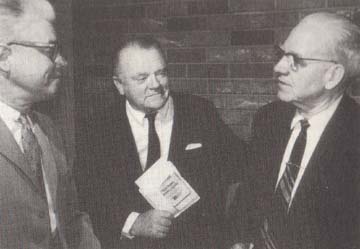

Edward Zern from American Motors, actor James Cagney, Arthur Carhart, December 1968. Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, Conservation Library Collection photos.

Carhart died in 1978, almost 20 years after the library was created. Although his career is dotted with many significant contributions to the American conservation movement, the library may be his greatest contribution to the movement today. His numerous conservation messages and ideas archived by the library will ensure that his legacy is preserved and that future conservationists can benefit from his wisdom.

References

Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center

Conservation Collection at the Denver Public Library

Kirk, Andrew G. "A Clean-Cut Outdoor Man." Collecting Nature: The American Environmental Movement and the Conservation Library. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2001. 19-47.

Wolf, Tom. "Ahead of His Time." Forest Magazine. Summer 2004.