Science

Scientific & Research Benefits of Wilderness

The scientific benefits of wilderness flow from many of the other values inherent to these protected landscapes, from ecological and geological to recreational and aesthetic. As John C. Hendee and Chad P. Dawson put it in their Wilderness Management text, "Wilderness is the world's living laboratory." It's true that wilderness science can teach us much about our world.

Social Sciences

Wilderness offers tremendously rich potential for studying the perspectives and behaviors of humankind. In the theoretical dimension as much as the empirical one, it has long been taken to represent a certain epitome of nature, and as such a useful prompt for investigating human perceptions of the natural world. Frederick Jackson Turner famously considered the formative influence of wilderness—and the idea of "taming" it—in his The Frontier in American History (1920). Another landmark exploration was Roderick Nash's Wilderness and the American Mind (1967).

Social scientists, however, have looked beyond people's reaction to wilderness itself to the impacts it has, as a setting and an experience, on human conduct and mindset. "How individuals relate to one another, how they react to stress and challenge, and how natural environments affect behavior are important topics for wilderness research," the authors of Wilderness Management note. For decades, sociological studies have looked into the value of wilderness as a therapeutic environment--formal inquiries echoing the personal and social benefits of wild country that everyone from Thoreau to Edward Abbey have espoused.

Physical Sciences

In wilderness areas, geologists, landscape ecologists, wildlife biologists, biologists, and other scientists study natural processes less influenced by humankind than in most other parts of the country. Outside wilderness, human impacts on ecosystems are often pervasive and complicated.

Larger wildernesses in particular offer the rare opportunity for ecologists to study broad, landscape-level ecosystem processes with only minimal human alteration. Among them are seasonal wildlife migrations and the complicated interactions of climate and biophysical systems.

Recent decades especially have highlighted the scientific importance of wilderness areas as refuges not just for ecological communities but also the disturbances that so vitally help shape them. When the Wilderness Act was passed, as Jerry F. Franklin and Gregory H. Aplet have written, scientists and resource managers believed that "wilderness ecosystems would remain unchanged over time, maintained in approximately the condition in which white explorers first found them."

That notion has been proven dramatically false: wildfires, volcanic eruptions, severe storms, and other disturbances profoundly affect most ecological landscapes. They seem particularly important in maintaining "patchy" habitat diversity—allowing more species to utilize a given landscape mosaic, and ensuring certain early-successional vegetation communities and their associated biota a continuing place in it.

Wilderness areas have allowed ecologists to track the long-term impacts of disturbances. For example, millions of acres of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness in the Klamath Mountains of southwestern Oregon burned in the 2002 Biscuit Fire, one of the biggest conflagrations in recent American history. While non-wilderness forestland that has been scorched is often salvage-logged, the burnt woods and shrublands of the Kalmiopsis serve as subject for ongoing investigations into natural post-fire succession.

Research Informing Management

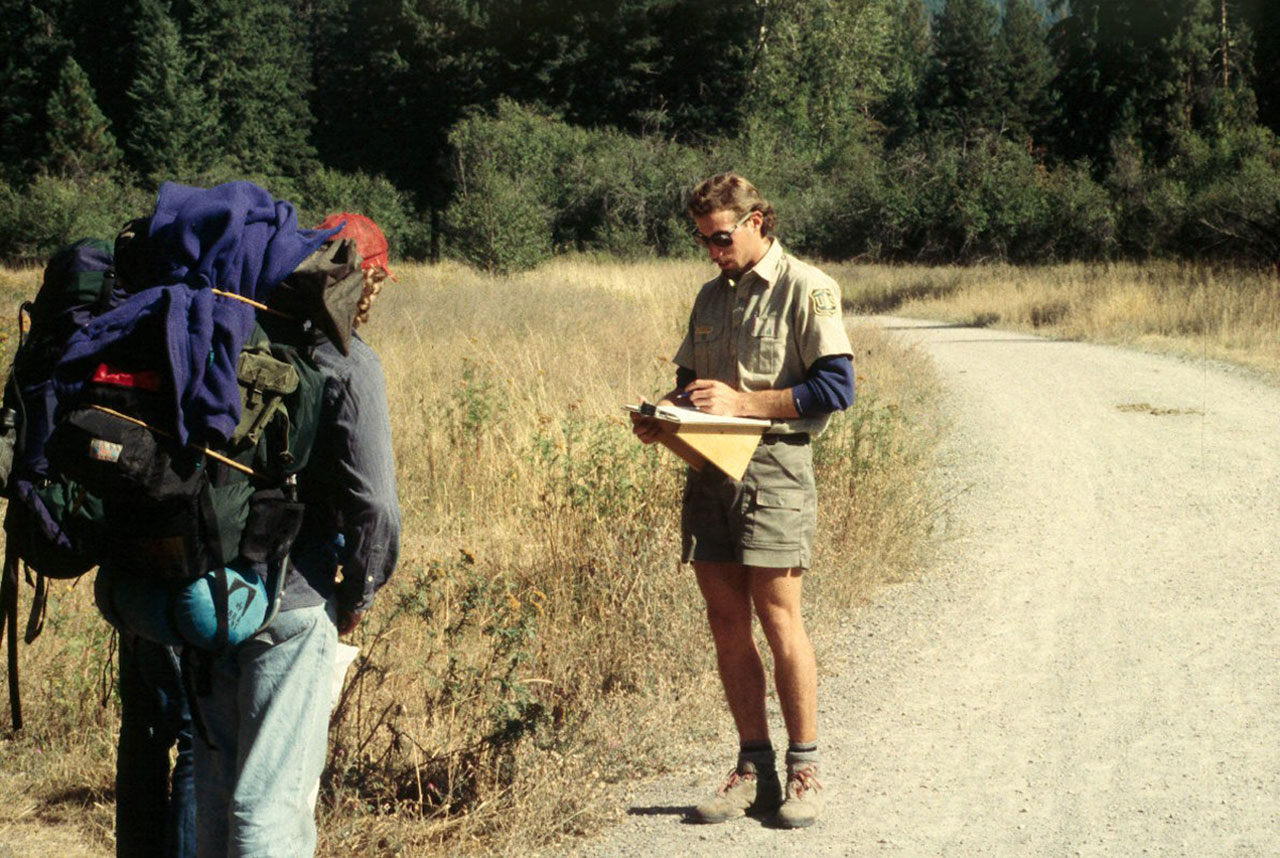

Social- and physical-science inquiries related to wilderness areas provide insights into human and ecosystem behavior, respectively, which are useful in their own right. Resource specialists and public land agencies can also use that same data to shape how wilderness areas are managed. For example, research found that local visitors to Montana's Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex were significantly more accepting of prescribed fires than non-local visitors, regardless of whether burns were proposed to restore the natural role of wildfire or to reduce hazardous fuels and the potential for fire to escape to non-wilderness lands.

Biological and ecological data help scientists understand potential threats to natural resources on public lands (and beyond), including those posed by climate change. One study on the threats to wilderness from invasive species and disease found that 46% of boreal toads at lower elevations with higher temperatures were infected with Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a lethal fungus, while only 10% of toads at higher, colder elevations were infected. The authors suggest that warming temperatures associated with global climate change may facilitate the spread of the fungus into previously unaffected areas.